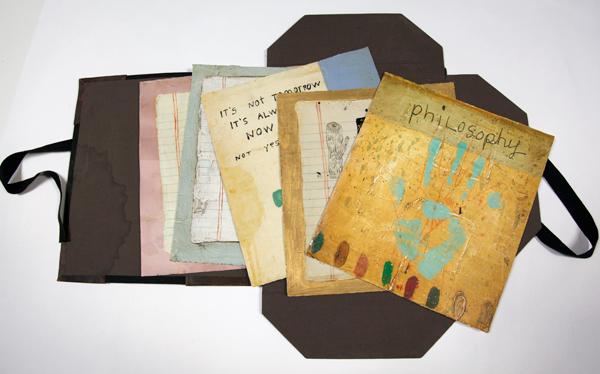

Artist's book: double-sided prints, portfolio, leather satchel

portfolio - 12 x 10.5 x 1 in; prints - 11 x 10 x 0.125 in

Edition of 20

Inspired by a suggestion from her colleague Jo Whaley, Squeak Carnwath’s Philosophy collects some of the artist’s most piquant and personal work in a format which takes the reader behind the scenes of her celebrated paintings. Philosophy is an artist’s book which doubles as a “facsimile archive,” as Carnwath puts it, of the studio artifacts which accumulate as she works on her trademark oil and alkyd canvases. Carnwath refers to these artifacts – the loose sheets bearing notes, drawings, color tests, quotations, and various other bits of information – as “the crazy papers.” Working with Donald Farnsworth in late 2009 and early 2010, the artist scanned dozens of the crazy papers, as well as passages from small paintings and from her “studio books” – lined ledgers into which she tapes clippings – combining and rearranging elements from all three sources to compose the 40 images in Philosophy.

While Carnwath still proudly calls painting “the queen of the arts” and drolly suggests that the crazy papers are “the little workers – [they’re] the hive, and painting is the queen,” Philosophy celebrates these intimate compositions as art objects in their own right. At the same time, the book offers an unprecedented encounter with Carnwath’s process, acting as a kind of concordance to the canvases: “The crazy papers,” she says, “are the diaries of the paintings. When I’m painting, I think of something, or I talk about a color I want to put down , or what I want to do the next day… They lead me into things I can do in the paintings. Then they kind of marry together so you don’t know which came first. ”

Philosophy’s pages were printed using a flatbed acrylic printer on paper textured with hand-brushed marble dust and gesso; the printed imagery was registered so as to align with the textures with uncanny precision. Carnwath happily describes viewers’ astonishment when she reveals that the lined notebook paper is actually made of modeling paste and pigment, and that lines apparently scrawled in pencil are in fact printed in acrylic ink. Farnsworth developed the process with printer Tallulah Terryll: “we’ve sculpted these pieces,” he says, “to be true to Squeak’s mark.” In a letter to poet John Yau, Farnsworth wrote of the book, “We are moving into strange and dangerous territory – printmaking that may raise some eyebrows… making textures that were, before this, the private playground of painting and sculpture.”

To Carnwath, the technique resonates with the work of American trompe-l’oeil artists John Frederick Peto and William Harnett, and with the paintings of her favorite artist, Rembrandt, in which objects are three-dimensionally sculpted from layers of thickly applied paint. “There’s illusion [in their work],” she says, “but there’s also a kind of literalness,” adding: “even as kid, I used to make fake maps on onion skin paper and burn the edges; I love facsimiles. And I like these kinds of experiments or loose objects that aren’t painting – that are an extension of it.”

In an essay on Carnwath, Karen Tsujimoto writes that “in [Rembrandt’s] hands, paint – the substance itself – became something real, and in the process, he was able to convey the idea that vision is a kind of touch.” The first page of the book places the artist’s handprint, life-size, under the eponymous “Philosophy,” suggesting a definition, an equivalence. Philosophy for Carnwath means a record of the hand, a form of physical inscription, as if to say: my body was here; this was a moment of my existence. Analogous to the sense of touch identified by Tsujimoto, the presence of the hand and by extension the body is a ubiquitous theme in Carnwath’s work even beyond its impasto and textured surfaces. From handprints to handwriting, from the palm reading chart to clippings and notes about obesity or longevity, the body is always present, grounding her personal idiom in a shared human reality.

Text becomes a physical mark in Philosophy, a record in the sense of the Latin recordari, from re (restore) and cor (heart) – something originating from and ultimately returning to the body. The book suggests that for Carnwath there is little distance between the works of Pascal and the grottos of Lascaux, between neat rows of typeset sentences in a scholarly treatise and untamed herds of bulls and horses traced in Prehistoric pigment on a cave wall. Both are simply marks made to illuminate existence. “Writing is creation,” Roland Barthes suggested in The Grain of the Voice, “and to that extent it is also a form of procreation. Quite simply, it’s a way of struggling, of dominating the feeling of death and complete annihilation. When one writes, one scatters seeds, one can imagine that…one returns to the general circulation of semences.” Carnwath echoes this sentiment in a 1990 interview in Cover magazine, discussing the handwritten passages in her work: “I love the way language looks… evidence of thinking. When I thought of using it, I thought of it as illumination. It is making visible my experience in the world, the fragility of being – on the cusp of being here and not being here.”

Philosophy balances its verbal content with passages of total silence, as when a coffee stain (apparently left by chance, but in fact intentionally imprinted by the artist) and the rigid lines of a leaf of ledger paper converge as if recording a single, silent moment in Carnwath’s studio. Where words do appear in her own distinctive hand, the artist is quick to point out that they are not quotations: “If they were, I’d have quote marks around them and I’d credit them.” The aphorisms and observations in Philosophy are Carnwath originals; while some may have taken inspiration from outside sources, they have all been given a new turn of phrase by the artist’s uniquely expressive voice and reflect multiple shades of meaning, illuminated by Carnwath’s world of color and consciousness.

– Nick Stone

show prices

Prices and availability are subject to change without notice.The copyright of all art images belongs to the individual artists and Magnolia Editions, Inc.

©2003-2025 Magnolia Editions, Inc. All rights reserved. contact us